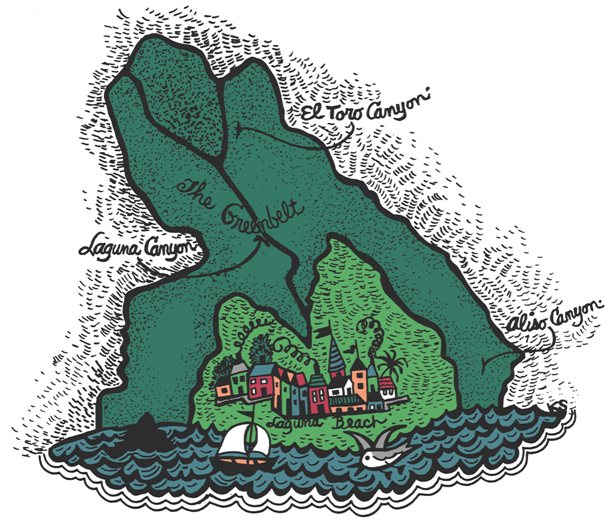

Aerial views show a beachside town lacking major access points; an enclave located equidistant from any multi-lane freeway. This is an exceedingly rare phenomenon in the nation’s sixth-most populous county. Pacific Coast Highway is the only way into town coming north or south and the lone inland route is Laguna Canyon Road.

A bird’s eye view of Laguna Beach also reveals that that the city is hemmed in by a crescent moon of protected land, called the Laguna Greenbelt. This swath of open space is actually made up of three major nature reserves—Crystal Cove State Park, Aliso and Wood Canyons Wilderness Parks, and Laguna Coast Wilderness Park. Each of these conservation areas was formed through major land purchases (both by the state of California and the city itself) and came with no small amount of help from motivated citizens.

The battle over Laguna Canyon was particularly historic, with locals and real estate interests pitted against one another in dramatic fashion over the course of decades. In 1986, the Laguna Canyon Conservancy was formed so that citizens could present a united front against the onslaught of development. Their first major success came in 1988, when the California Coastal Commission voted down the proposed expansion of Laguna Canyon Road. Later that same year, the Irvine Space Initiative increased the Laguna Greenbelt and a $10 million grant tied to California Proposition 70 allowed the city to continue buying land for the sake of preservation.

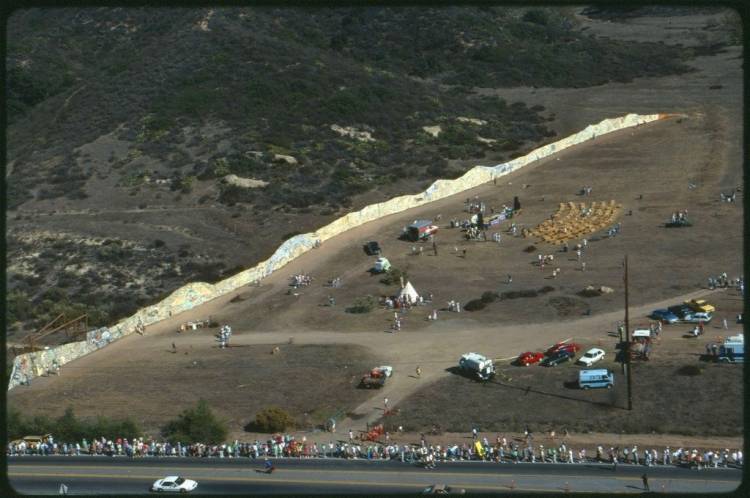

The two iconic events of this long-running saga came in 1989. First, there was “The Tell”, a 636-foot long photomural created by artists Jerry Burchfield and Mark Chamberlain. It consisted of more than 60,000 photos—snapshots of life in Orange County. With each image (many of which were contributed and pasted to a plywood wall by volunteers), the artists slyly suggested that the pressures of development were threatening the city’s way of life.

“It is a flag, if you will, something to rally around,” Mark Chamberlain said of the wall to the LA Times in 1989. “People have been thirsting for a direct way to express their feelings.”

The piece was staged at the site of a proposed toll road that would bisect Laguna Canyon. This corridor would facilitate a 3,200-home development by the Irvine Company, plus 82 acres of commercial development and a golf course.

The artwork, the perfect protest-medium for Laguna Beach, received widespread media coverage. The piece, which visitors can see partially recreated at Nix Nature Center in Laguna Canyon, drew people into the conservation conversation and built a groundswell of local support.

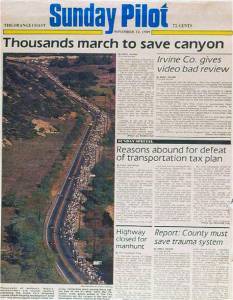

Later that same year, the efforts of Laguna locals culminated with “The Walk”—a protest that began at the Festival of Arts grounds. 8,000 people marched toward the proposed development and cheered speeches by Laguna Beach’s then mayor, Lida Lenney and members of the city council.

By 1990, locals had overwhelmingly approved a property tax increase in order to fund the first stage of purchasing the land from the Irvine Company. That same year, The Laguna Canyon Foundation was formed to complete these purchases and act as wardens of the canyon.

This victory continues to define the very spirit of the city and though various interests are still trying to hash out the perfect balance between access and preservation (the 73 toll road was eventually built in 1993), the safety of Laguna’s Greenbelt isn’t up for debate.

In the winter the stunning swath of protected lands are verdant and lush; in the summer, the pitted sandstone shelves stand out more and the grass dries (much of it is devoured by visiting Peruvian goats). Regardless of the season, it’s an area rich in history, teeming with wildlife, and ripe for adventure.

This report was complied with help from Laguna Greenbelt Inc. (WWW.LAGUNAGREENBELT.ORG) and the Laguna Canyon Foundation (WWW.LAGUNACANYON.ORG) both of which work to protect the canyon and make it accessible to visitors and locals alike.